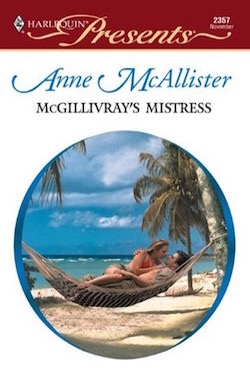

Excerpt: McGillivray’s Mistress

Book 1: Pelican Cay Series

Chapter One

Some people called it “sculpture.” Lachlan McGillivray begged to differ.

As far as he was concerned, the monstrosity on the beach in front of his elegant upscale Moonstone Inn was — pure and simple — “trash.”

What else could you possibly call the nightmare — ten feet high and growing — that had begun to arise a month ago from the flotsam and jetsam that washed up on Pelican Cay’s beautiful pink sand beach?

“Delightfully inventive,” an article in last Sunday’s Nassau paper called it. “A creative amalgam,” the Freeport newspaper had said. “Fresh and thought-provoking,” the art critic from a far-reaching Florida daily claimed.

“Deliberate nose-thumbing,” was Lachlan’s opinion. It was just Fiona Dunbar having a go at him.

Again.

Fiona Dunbar had been a pain in the posterior – his posterior! – since he and his family had moved to the small Bahamian island when Lachlan was fifteen.

Life in suburban Virginia with its soccer leagues and its supply of cute blonde cheerleaders had been all he’d ever wanted back then. Being uprooted and transplanted to a remote Caribbean island just so his father could satisfy a need for wanderlust at the same time that he pursued his career as a family physician had infuriated Lachlan, though the rest of the family had come willingly enough.

In fact his brother Hugh, two years younger, and his sister, Molly, six years his junior, had been delighted to trade their stateside existence for life for the sticks.

“There’s nothing to do there!” Lachlan had complained.

“Exactly,” his father had said happily, looking around at the miles of deserted beach and the softly breaking waves and then up the hill at the higgledy-piggledy scatter of pastel-colored houses, its three hundred and fifty-year old rusting cannon, and the half-over-grown cricket field with its resident grass mowing horse,. “That’s just the point.”

Lachlan hadn’t been able to see it then. He’d thought it was the most boring place on earth, and he’d said so often.

“So leave,” Molly’s best friend, the supremely irritating Fiona Dunbar had said, sticking her tongue out at him.

“Believe me, carrots, I would if I could,” he’d replied.

And he had — as soon as his acceptance had come from the University of Virginia. He’d been gone four years, returning only occasionally to see his parents. Then he’d gone on to Europe to play soccer in England, Spain and Italy, and had come back even less often, and then only to regale family and friends with tales of life in the fast lane.

But oddly, the longer he was gone, the more he found himself remembering the good things about Pelican Cay. The more he’d awakened in the morning in this big city or that one and listened to the birds cough, the more fondly he’d remembered waking to island birds and island breezes. The more he moved frenetically from one place to another, the more he appreciated the slower island pace. He liked the autobahn and the Louvre and the centuries of European culture. He liked French cuisine and Italian delicacies and Spanish wines. But sometimes he missed a slow amble down a potholed road, a one-room island historical society, the 350 year old rusty cannon, a plate of conch fritters and a long cold beer.

A couple of years ago, when Hugh had come back to start his island charter service, Fly Guy, in Pelican Cay, even though their parents had moved back to Virginia, Lachlan had thought his brother had the right idea.

“I’ll probably come back when I retire, too,” he’d said.

Hugh had raised dark brows. “And do what?”

Hugh had gone to college, then into the US Navy where he’d been a pilot for eight years. But always a beachcomber at heart, he’d finally bolted the regimented world and was never happier than when he was lying in a hammock, drinking a beer and watching the waves wash up on the shore.

That was not Lachlan. Lachlan had always had goals. He’d made up his mind at the age of twelve that he was going to be “the best damn goalkeeper” in the world and he’d never swerved from his pursuit of that.

While his parents had scowled at his profanity, they’d admired his determination – and his success. He’d spent sixteen years as one of the best goalkeepers in the world. But even he couldn’t play in goal forever.

It was a young man’s game. A young healthy man’s game. Retirement had come last summer, at the age of thirty-four, when a serious knee injury had so compromised his quickness that Lachlan knew it was time. His mind was as quick as ever, his anticipation as great. But he would never get his edge back physically. And he refused to play down a level.

There was only one place to be – at the top.

Fortunately, he’d been buying up real estate for the past four years. Eighteen months ago he’d decided on his post-soccer career and had, with his customary determination, set about accomplishing it. First he’d bought the Mirabelle, a small elegant inn at the far end of Pelican Cay. It was already a thriving business and he could step right in whenever he wanted to. That made sense to everyone.

But when the Moonstone came on the market and he bought that, everyone had been appalled.

“The Moonstone? What the hell are you going to do with that?” Hugh had demanded The eighty-year-old three story clapboard structure with its peeling paint and sagging verandas had looked like nothing but work to him.

“I’ll restore it and refurbish it,” Lachlan had said, relishing the prospect.

“What do you know about building restoration?” Hugh raised skeptical brows.

And Lachlan had had to admit he’d known very little. But the challenge drove him. He’d thrown himself into it with vigor and enthusiasm. He’d learned and studied and worked. He’d hired lots of help, but he’d been right in there doing his part, determined to “turn it into the best damn inn in the Caribbean.” It had been open over a year now, and was doing very well.

“Pretty soon,” Lachlan had told Hugh not long ago, “it will become the destination of choice for active discriminating travelers, those who have the brains and the soul to appreciate the true beauty of the islands.”

Hugh had stopped humming along with Jimmy Buffett long enough to look up from his hammock and laughed. “The way you appreciated it?”

But Lachlan just shrugged him off. “You’ll see. It will be great. For the tourists and for the island. The Mirabelle will still take the old guard — those folks who have been coming for years. But the Moonstone will attract the newcomers. And that will be good for Pelican Cay. The island could use a kick in the butt. Something has to jumpstart the economy. Fishing’s not enough now. They need to diversify and – ”

“The zeal of the converted,” Hugh had shaken his head and closed his eyes.

Which was true enough, Lachlan supposed. As much as he’d resented Pelican Cay all those years ago, all he could see were possibilities now —

And a ten foot monstrosity every time he opened the blinds.

He scowled out the window again. The monster seemed to have gained another arm overnight. A bent driftwood spar thrust upward from its side, with something not quite discernible in the early morning half-light fluttered from its outflung hand.

Plastic? Seaweed? Whatever it was, it taunted him.

He turned away again and flung himself into the chair at his desk and tried to focus on the correspondence that his assistant and the Moonstone’s manager, Suzette, had left for him to sign and the mail that had arrived while he was gone.

He’d been away since Saturday, having flown to the Abacos to oversee some renovations at the Sandpiper, the next in the series of inns he was renovating. He’d returned very late last night and had deliberately avoided glancing the thing when Maurice, one of the island’s taxi drivers, had dropped him off at the door.

Bad enough that he’d felt compelled to open the blinds this morning to see what further effrontery Fiona had achieved.

He tried to ignore it and get back to the business at hand. He had plenty of pressing things to worry about. But his fingers strangled his pen as he scanned and signed half a dozen letters, then read the post that had arrived since he’d left.

The last one was a response to a letter he’d dictated in the spring. The Moonstone had done well all on its own during the winter months. Sun-seeking snowbirds from the northern climes had filled the rooms every night. But summer and fall occupancy was more problematic. So he’d sent notice of its existence to several exclusive tour agencies and travel magazines, encouraging them to send a representative to see what the Moonstone had to offer.

A couple of the tour companies had, including the impressive Grantham Cultural Tours whose founder was arriving later this week. This particular letter, however, was a response from an upscale travel magazine called Island Vistas.

“Will be arriving next week,” the tour rep had written. “The ‘quiet island elegance’ you mention hits exactly the right note. The Moonstone sounds exactly like the sort of place our readers love.”

Quiet island elegance! Oh yeah, right. With a ten foot steeple of trash growing on its doorstep?

“Well, it’s quiet,” Hugh had said cheerfully last week when Lachlan had complained about it. He was enjoying Fiona’s tactics as they weren’t aimed at him. “Doesn’t make a sound. Does it?”

It didn’t have to. It was a visual scream. It was an affront to him – and to the sensibilities of the inn’s guests. And if that wasn’t annoyance enough, there were always the bagpipes.

“Bagpipes?” Hugh had stared at him.

“Wait,” Lachlan had raised a hand to still his brother’s protest. “Just wait.”

And after they’d eaten in the inn’s dining room, he’d insisted Hugh sit on the deck of the Moonstone and wait until night fell on Pelican Cay — and the miserable tremulous bleat and warble of an off-key Garryowen drifted toward them on the breeze.

Hugh’s stunned expression had given Lachlan considerable satisfaction. But he would gladly have foregone it, for the pleasure of hearing nothing but the waves breaking on the sand. He arched his brows to say Now do you believe me?

“You don’t know it’s Fiona.”

“Who the hell else could it possibly be?”

Fiona Dunbar had been systematically driving him crazy since she was nine years old.