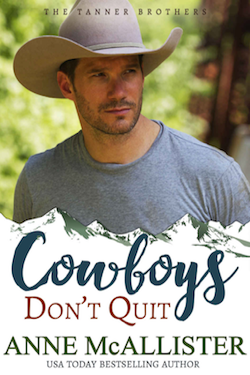

Excerpt: Cowboys Don't Quit

Book 2: Tanner Brothers Series

Chapter One

He was dreaming again.

The same dream. Always the same. They were body surfing near the pier in Manhattan Beach, he and Keith, laughing, joking, competing for the biggest wave, the steepest drop, the longest ride. They were showing off for Keith’s fans and the other people on the pier who stood watching, waving, smiling.

He saw Jillian there, too, braced against the railing, her long blonde hair tangling across her face in the wind as she waved to them, then looked out to sea and pointed.

He looked over his shoulder. So did Keith. The swell was already noticeable, building now, moving toward them.

“Wave of the day!” Keith yelled, grinning and moving into position, beginning to stroke toward shore.

He watched Keith go, then he moved, too, slower, as he always was in the water, but still in time. He caught the momentum, merging with the force of the wave, rising on its crest to see the water and the foam and the beach spread out before him. He caught a glimpse of Jillian leaning over the railing, watching. He spied Keith just ahead, already into the fall.

And then he fell, too, as the wave crested, curving under, dropping him headlong into the backwater. It pounded down on top of him, pressing him into the ocean floor even as it dragged him along. He felt a thump. His body collided with Keith’s. Arms and legs tangled in the power of the wave. And then they shifted, separated. He felt Keith’s fingers grab for him. They clutched, touched, clung. Then slipped away.

Away …

He opened his mouth to call. Keith! But the water choked him. Gagged him. Pressed down upon him, swirling and pounding, grinding him into the sand, crushing his lungs, burning his throat . . . Then for a moment, blessed air. And just as suddenly the wet suffocation was back, choking his mouth, covering his nose . . .

Luke jerked awake. Hank, the old herding dog, was licking his face.

“Damn.” He shuddered and pushed her away. “Hell of a way to say good mornin’,” he grumbled at her, but he knew it wasn’t Hank’s fault. It was the dream.

Always and, it seemed, forever — the dream. And it wasn’t even the way it had happened, for God’s sake.

It — Keith’s death.

Even now, almost two years later, it was hard to think of Keith Mallory being dead. Intense, dynamic, irrepressible Keith — mover and shaker, dreamer and doer, one of America’s best-loved actors — had always had more to live for, more to give than anyone.

Luke’s fists clenched futilely against the lingering feel of Keith’s grip slipping away. He drew a ragged breath.

In reality he’d had no chance to even come that close. He hadn’t even been in the water.

Luke sat up on his cot now, shivering still, though not so much from the cold as from the memory. He drew another breath of the crisp Colorado mountain air and tried to shake the shivers off. But even though it was July already, at close to nine thousand feet, it didn’t ever get very warm until the sun was up and what memories didn’t accomplish, the temperature did.

He pulled his knees up to his chest and wrapped his arms around them, his body trembling in a now familiar cold sweat. He rubbed a hand across his wet face, tasting salt amid the dog slobber. Tears. He rested his head against his bent knees and tried to steady his breathing.

Keith. Oh, God, Keith. I’m sorry. I wish it was me.

The dog nudged his shoulder and tried to lick him again. Luke looped an arm around her neck and rubbed his face against her fur. Then he scrubbed a hand across his eyes and hauled himself to his feet. There would be no sleeping now, no point in even trying.

Not that he wanted to. Not when he dreamed.

He could tell from the faint light filtering through the window of the rough log cabin that it wasn’t quite dawn. The sky to the east was still more dark gray than rose. But there was nothing to be gained by staying in bed. He would just lie there remembering what he would give his soul to forget.

He picked up the coffee pot, let himself out into the crisp mountain air, and headed toward the spring. He filled the pot, then carried it back to the cabin, dumped in the coffee, and started a fire on the small propane stove.

He made himself concentrate on each task as he performed it. He could’ve done it all mindlessly, but he knew better now.

Whatever part of his mind he didn’t keep focused on what he was doing would be on the dream or, even worse, on the memories that caused it.

He rubbed his fingers together. He couldn’t feel the clutch of Keith’s fingers anymore. Sometimes the feeling lasted for hours. Not, thank God, today.

While the coffee was heating, he scrubbed his face with some of the water he’d brought up the night before, then dragged a comb through his shaggy dark hair. He could tell by feel that the next time he went into town he’d better stop by Bernie’s and get a haircut. Not that he’d be going anytime soon. Lots of camp men these days came down off the summer range every week or so, but they had friends, family, people to see, mail to pick up, a life to keep in touch with in town. Luke didn’t. Nor did he want any. He set his hat on his head and tugged down the brim, then went back to the stove.

The coffee was hot. He poured himself a mugful and stood staring out the small window, his hands wrapping the cup, making himself think about what he needed to do that day. Chivvy cattle up out of the creek bottom. That was a given. They were like magnets, those cows. You barely got them up to the head of the draw and left them and they drifted right back down again. Or got spooked and ran back again. He needed to circle up around and check on some near the National Forest land. See that the gates were closed. If one wasn’t he’d have his day’s work cut out for him, for sure.

In the early morning light he could look down across the meadow and see three of his horses already lurking by the quaky fence waiting for him to come out and holler ’em down and grain ’em. He didn’t even need to holler anymore. He’d been doing it for more than a year now — long enough that they knew what to expect.

He took another swallow of coffee, then set his cup down and poured out food for the dogs. There were two others besides Hank — a scruffy looking catch dog called Muff, and another Border collie named Tommy. They brushed against his legs as he poured their food out for them. Hank nudged under his hand, her pointy nose wet and cold against Luke’s fingers. Luke rubbed her under the chin.

The panic was gone now. The pressure had eased on his lungs as the dream faded and the sunrise brought light and clarity and color to the mountain meadow he called home.

Breathing more steadily now, Luke finished his cup of coffee. He made and ate a quick breakfast, then headed out to wrangle his horses.

Some days were more work than others. Today &emdash; because of the dream; he might as well admit it &emdash; Luke made it more work than it was.

He moved twenty head of cattle up out of the creek bottom, doctored some foot rot, rode the fence all along the National Forest line — and was glad he did, too, when he found one of the gates left open by some careless hikers.

He rounded up half a dozen cattle and brought them back down on the right side of the fence, then circled over through a stand of quaking aspens toward the creek. That was when he found that young Soler bull caught in the middle of a willow patch.

Bulls weren’t the easiest critters to deal with at the best of times, and when they’d been stuck as long as this bull likely had been, their tempers weren’t exactly sweet. The Soler was no exception.

Luke could’ve left him. He was tempted. Wasn’t anybody looking over his shoulder to see him. But a guy wasn’t doing his job if he didn’t. And a dreamless sleep came more often when he was so dead tired he couldn’t move.

Getting the bull out of the willows ought to go a ways toward accomplishing that.

He laid a loop over the bull’s head, then alternately dragged and chivvied the animal while Hank and Tommy nipped and prodded. It took damn near an hour. And since he was chivvying on foot, not dragging on horseback when the bull finally broke free, he barely missed a kick in the ribs.

And that was when he saw the bull had foot rot.

“Son of a gun,” he muttered. “Must be my lucky day.”

He didn’t ride back over the rise that looked down on his camp till almost six when the sun was already dipping down to touch the mountains to the west.

He was dirty, and sweaty, tired and sore. The bull might’ve missed his ribs with his first kick but he hadn’t missed his shin when Luke had sidestepped his horse in close enough to give the bull his injection.

Still, physical pain wasn’t what kept him awake or made him dream.

Tonight he reckoned he’d earned his sleep. And he thought he just might get it, too. Or he did until he saw someone sitting by the door to his cabin.

He scowled, squinting, trying to see who his company was. Nobody he’d invited, that was damn certain. Since he’d moved up the mountain a year ago last spring, Keith hadn’t encouraged visitors. Jimmy from the ranch house came up now and then to bring Luke provisions or a coffee cake or some cookies his bride Annette had made. His only other visitor was Linda Guttierez’s son, Paco.

“You don’t want him around, you send him away,” Linda had told him from the first. But Paco’s dad had died three years ago and Luke could remember how he’d felt when his own dad had died. He hadn’t had the heart to send the boy away.

Besides, talking with Paco was a form of penance since all the kid ever wanted to do was hear about Keith. He probably knew by heart every movie Keith Mallory had made and he took great joy in asking Luke about the ones he’d worked on. Luke wondered when he’d realize that it was Luke’s fault his hero was dead.

He sat up a little straighter in the saddle now, trying to guess his visitor’s identity. Whoever it was saw him and got up, beginning to move toward him now.

Hell’s bells. It was a woman.

A tall and slender woman in jeans that hugged curves no cowboy’d ever have. And long blonde hair that tangled across her face in the evening breeze.

Luke felt as if the bull had kicked him right in the gut.

It was Jillian.